In an era where digital products shape our habits, choices, and even our trust in brands, the difference between success and failure often hinges on something deceptively simple: usability. For CEOs leading early-stage startups or fast-growing tech companies, understanding the foundations of good design is no longer optional. It is a strategic asset. Don Norman’s The Design of Everyday Things, originally published in 1988 and thoughtfully revised over the years, remains one of the most influential and relevant works on user-centered design. While the technologies have evolved—touchscreens, AI interfaces, connected devices—the core principles Norman articulates are more urgent today than ever.

This book isn’t a technical manual for designers. It’s a powerful lens for decision-makers to see how products actually succeed or fail in the hands of real people. CEOs often focus on vision, funding, and growth, but usability is what makes products lovable—and shareable. A great interface doesn’t just delight users; it reduces churn, increases engagement, and builds trust. Norman’s insights equip leaders to ask the right questions, foster the right culture, and make better product decisions from the start.

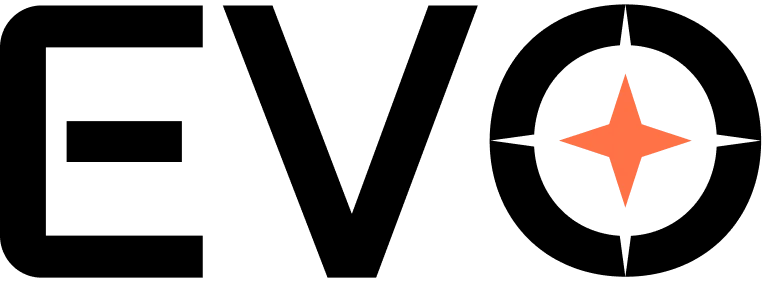

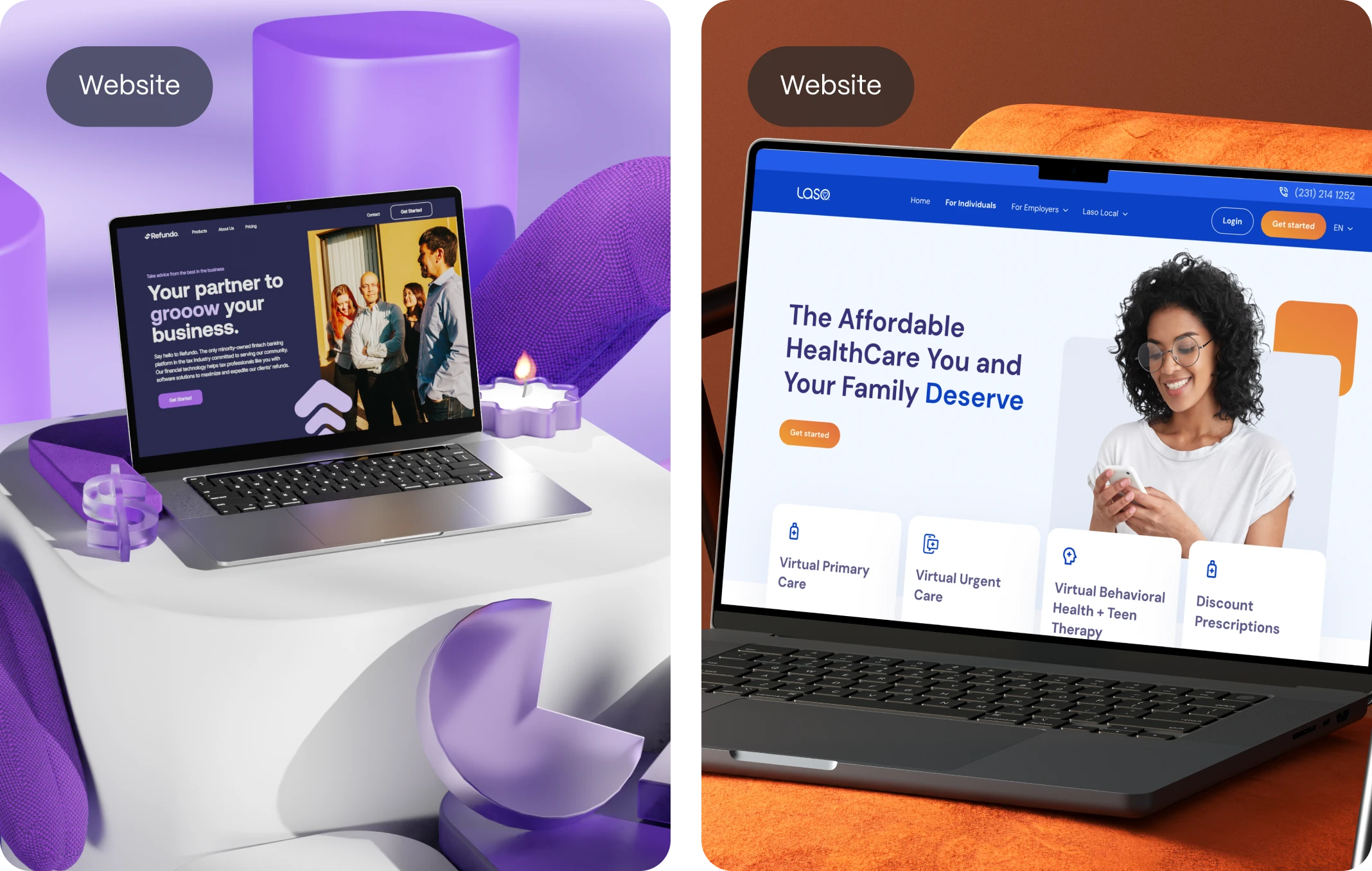

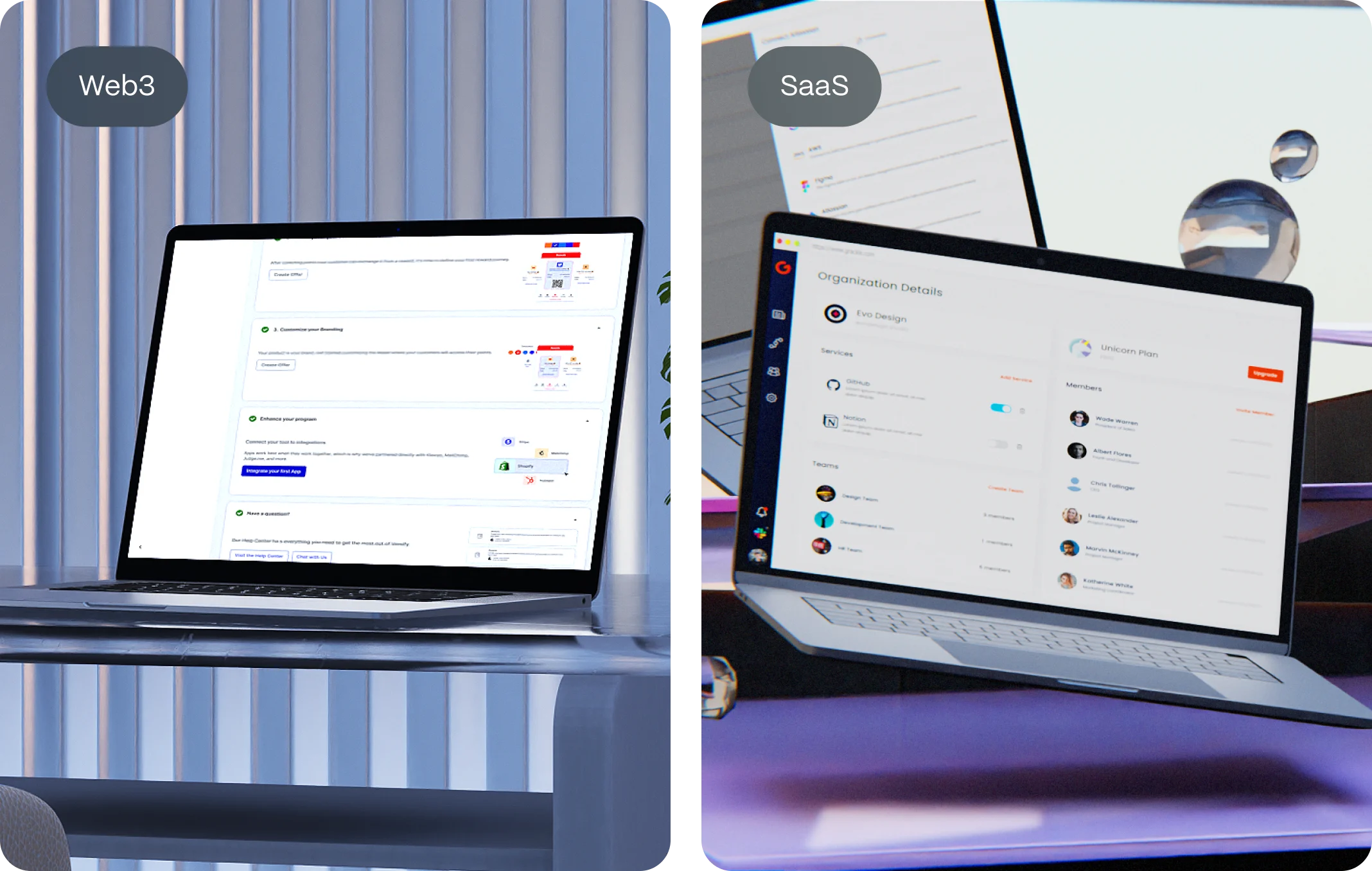

At Evo Design, we decided to revisit and review this timeless book not as a tribute to its legacy, but because of its continued relevance to the real-world challenges startups face today. Every week, we work with teams trying to bridge the gap between great ideas and usable, scalable solutions. This review aims to distill Norman’s wisdom into actionable reflections that product leaders, founders, and innovation teams can apply to their journey. Whether you’re launching your first app or redesigning a SaaS platform, the lessons from The Design of Everyday Things will sharpen your instincts and elevate your impact.

The Everyday Genius of Don Norman’s Vision

Published originally in 1988 and later revised, The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman remains one of the most influential texts in the field of design, usability, and human-centered innovation. It is not merely a book about how things should look or function—it is a blueprint for empathy in the design process. As a cognitive scientist and usability engineer, Don Norman introduces readers to a world where doors, faucets, and switches are not trivial annoyances, but powerful case studies on human behavior, memory, frustration, and perception. What makes this book timeless is how it elevates the seemingly mundane to a matter of strategy, psychology, and human well-being.

At the core of Norman’s argument lies a deceptively simple premise: if users fail to use a product correctly, the problem lies not in the user but in the design. This philosophy marks a dramatic shift from a blame-the-user culture toward a framework where designers are responsible for crafting intuitive, comprehensible interactions. In today’s digital-first world, where interfaces multiply faster than ever, Norman’s ideas are not only relevant—they are essential. His voice is both critical and constructive, guiding designers to examine their choices with a sense of moral clarity and a scientific lens. The result is a compelling journey through the anatomy of design failures and the principles that can solve them.

Design as Communication — Affordances, Signifiers, and Feedback

One of the most profound contributions of The Design of Everyday Things is the introduction and clarification of key design concepts: affordances, signifiers, mappings, constraints, and feedback. These terms—now foundational in design and HCI (Human-Computer Interaction)—form the language through which Norman critiques and rebuilds the user experience of objects and interfaces.

Affordances refer to the possibilities for action that an object offers. A door handle affords pulling; a flat metal plate may afford pushing. But affordance alone is not enough. Norman introduces the concept of signifiers—the indicators that communicate how to use something. A handle may afford pulling, but without a visual or tactile cue—a signifier—the user may still get it wrong. He illustrates this with “Norman doors,” a now-famous term for poorly designed doors that confuse users about whether to push or pull. These seemingly trivial frustrations highlight a deeper issue: design without consideration of human psychology.

Feedback, too, is central to Norman’s framework. A good design informs the user of the result of their action. When you press a button and the elevator lights up, or when a computer icon animates after a click, you are receiving feedback. Without it, users are left uncertain, repeating actions or assuming failure. Norman’s examples—ranging from microwave ovens to digital controls—show that good feedback is not optional; it is essential for trust and flow.

By identifying and naming these principles, Norman provides more than academic terminology—he offers a practical toolkit. Designers, engineers, marketers, and product managers alike can learn to ask the right questions: Does this product suggest its use clearly? Are the actions understandable and the results visible? Norman’s clarity is one of the book’s greatest strengths, and his examples make abstract ideas tangible.

Human Error and the Psychology of Everyday Action

In The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman explores the phenomenon of human error not as an individual failing, but as a systemic issue often born from poor design. He argues that what we call “user error” is, in reality, design error. Devices that are unintuitive or require users to memorize steps or symbols without aid are setting them up to fail. In this sense, Norman positions the designer as an enabler—or an obstacle—of success.

He introduces the concept of the seven stages of action: forming a goal, forming the intention, specifying the action, executing the action, perceiving the system state, interpreting the state, and evaluating the outcome. This model functions as a lens through which designers can assess how well a product supports the user’s cognitive process. When a gap appears—between intention and execution or between perception and interpretation—errors are likely to occur. This breakdown is not due to human weakness, but to the system failing to bridge that cognitive gap.

Norman also discusses two types of errors: slips and mistakes. A slip happens when the user has the correct intention but executes it incorrectly—such as typing the wrong letter or turning the knob the wrong way. A mistake, on the other hand, occurs when the user’s intention itself is wrong, often due to incorrect mental models or lack of understanding. A good design mitigates both. It makes slips harder to commit and mistakes easier to avoid by providing context, constraints, and clear feedback.

This psychological approach to design is what sets Norman apart from most industrial or aesthetic design commentators. He doesn’t merely suggest that designers make things easier to use; he explains how users think, behave, forget, and adapt. This human-centric perspective remains a radical call to action for anyone shaping the experience of a product, service, or system.

Mapping, Constraints, and the Art of Intuitive Use

One of the most illuminating sections of Don Norman’s book concerns mapping—the relationship between controls and their effects. A well-designed product aligns its interface with the mental model users already possess. For example, stove controls that are arranged in the same layout as the burners make operation intuitive, whereas a linear or abstract arrangement requires memory or guesswork. Norman stresses that good mapping reduces cognitive load and increases speed and accuracy.

Closely tied to mapping are constraints. These are the design features that limit the ways a user can interact with a product, often guiding them toward correct usage. Norman breaks down constraints into four types: physical, cultural, semantic, and logical. Each plays a role in preventing errors and clarifying purpose. A USB plug, for example, has a physical constraint—it only fits one way. Cultural constraints are based on learned conventions (like red meaning “stop” or “danger”), while semantic constraints rely on context (a seat faces forward in a car). Logical constraints involve process of elimination—if one button is already pressed, it’s logical the other is next.

These principles may sound straightforward, but Norman’s genius lies in how he brings them to life with examples that resonate. From the layout of light switches to the cryptic buttons on remote controls, he shows how thoughtless design introduces confusion, hesitation, and sometimes even danger. And yet, when mapping and constraints are applied effectively, the result is elegant and empowering. Products “disappear” into the background, allowing users to act without friction.

In many ways, this chapter encapsulates Norman’s larger argument: good design is invisible. It doesn’t require explanation or manuals. It doesn’t rely on cleverness. It flows with the user’s intuition and respects their mental models. For startup founders and product designers, this insight is not only philosophical—it is a competitive advantage.

The Role of Mental Models in Design

One of the most intellectually rich contributions of The Design of Everyday Things is its exploration of mental models—the internal explanations that users form to understand how systems work. These models may or may not reflect the actual mechanics of a device or interface, but they shape behavior and expectations in powerful ways. When mental models align with actual system behavior, users feel confident, capable, and in control.

Norman emphasizes that users do not read instruction manuals. Instead, they rely on experience, intuition, and visible clues. If a product behaves in ways that are consistent with past experiences, users are likely to succeed. But if there is a mismatch between the user’s mental model and the product’s actual logic, confusion arises. This is where design can either reinforce correct understanding or deepen the divide.

The implications for product teams are vast. Designing with mental models in mind means more than choosing the right icons or colors—it means understanding the cognitive shortcuts people use to make sense of the world. A trash bin icon on a desktop interface works because it taps into a real-world concept. Dragging a file into it feels natural. But if the file disappears with no way to undo the action, the designer has betrayed the mental model.

Norman urges designers to build conceptual models that are coherent and transparent. When the underlying logic of a product is reflected in its interface, users can learn by doing. Mistakes become part of the exploration, not a source of frustration. In a time when digital interfaces have grown increasingly complex—spanning touch, voice, gesture, and automation—this lesson is more vital than ever. A product that respects mental models not only reduces user friction but also builds trust, loyalty, and satisfaction.

Design for Error Recovery and Forgiveness

In The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman makes a compelling case that design must account not only for correct usage but also for inevitable error. No matter how intuitive or logical a system may be, humans are fallible. They click the wrong button, forget a step, misread a symbol. A good design anticipates these moments and offers users a way out—a chance to recover, learn, and continue without penalty.

Norman introduces the idea of forgiving design, which builds tolerance into the system. Think of the “undo” function in most modern software. It allows users to experiment without fear. If a design does not allow for reversal, users may hesitate, second-guess themselves, or abandon the task altogether. Confirmation dialogs, autosaves, and visual warnings are examples of mechanisms that make interaction safer and more humane. These are not luxuries—they are foundational to user trust.

Equally important is the principle of graceful failure. When things go wrong, as they inevitably will, the product should respond in a way that informs and assists the user, not scold or confuse them. Clear, actionable error messages, contextual tips, and visual indicators of problem areas create a sense of support. The user feels guided, not blamed. Norman draws from examples like cryptic error codes on printers and microwaves—cases where the failure is made worse by lack of feedback or context.

What emerges from this chapter is a call for responsibility. Designers hold the power to create systems that either amplify human error or protect against it. By designing with error in mind—not as an anomaly but as a certainty—products become more resilient and inclusive. In a business landscape where user satisfaction translates directly into loyalty and revenue, this mindset is not only ethical but strategic.

The Evolution of Design in a Technological World

Don Norman does not limit his analysis to mechanical doors or remote controls. In the latter chapters of The Design of Everyday Things, he expands his scope to address how the rapid evolution of technology is reshaping the role of design. As interfaces shift from analog to digital, and from static to adaptive systems, the stakes for usability grow significantly. The designer is no longer dealing with simple tools but with complex ecosystems—smartphones, dashboards, home automation systems, software platforms—that interact with users in increasingly layered ways.

This chapter offers insight into the challenges of modern design. New technologies often prioritize innovation over usability, leading to products that are feature-rich but overwhelming. Norman argues that good design must act as a filter and translator—it must make the complexity of the system accessible to the user without revealing its entire internal architecture. That means offering clarity, not clutter. Relevance, not redundancy.

Norman touches on the concept of progressive disclosure, where advanced functions are hidden from beginners and revealed as needed. This respects both novice and expert users, allowing each to operate at their comfort level. He also emphasizes the need for consistency across platforms. Users now engage with brands and products through multiple devices—desktop, mobile, voice assistants—and their mental models must be supported across each.

The core message here is that as technology grows more capable, design must grow more thoughtful. Startups, in particular, are often tempted to launch fast and iterate later, but Norman’s framework reminds us that poor initial design can damage credibility, confuse users, and slow adoption. The best digital products of today—like those by Apple, Google, and Airbnb—succeed because they treat interaction design as foundational, not ornamental.

Human-Centered Design: A New Standard for Innovation

One of the most enduring contributions of Don Norman’s work is his advocacy for human-centered design (HCD). This methodology insists that products and systems must be designed around the needs, behaviors, and limitations of real people—not around technology, business constraints, or assumptions. Rather than forcing users to adapt to poorly conceived tools, human-centered design ensures that the tool adapts to the user. This, Norman argues, is not just a design choice—it is a moral and practical imperative.

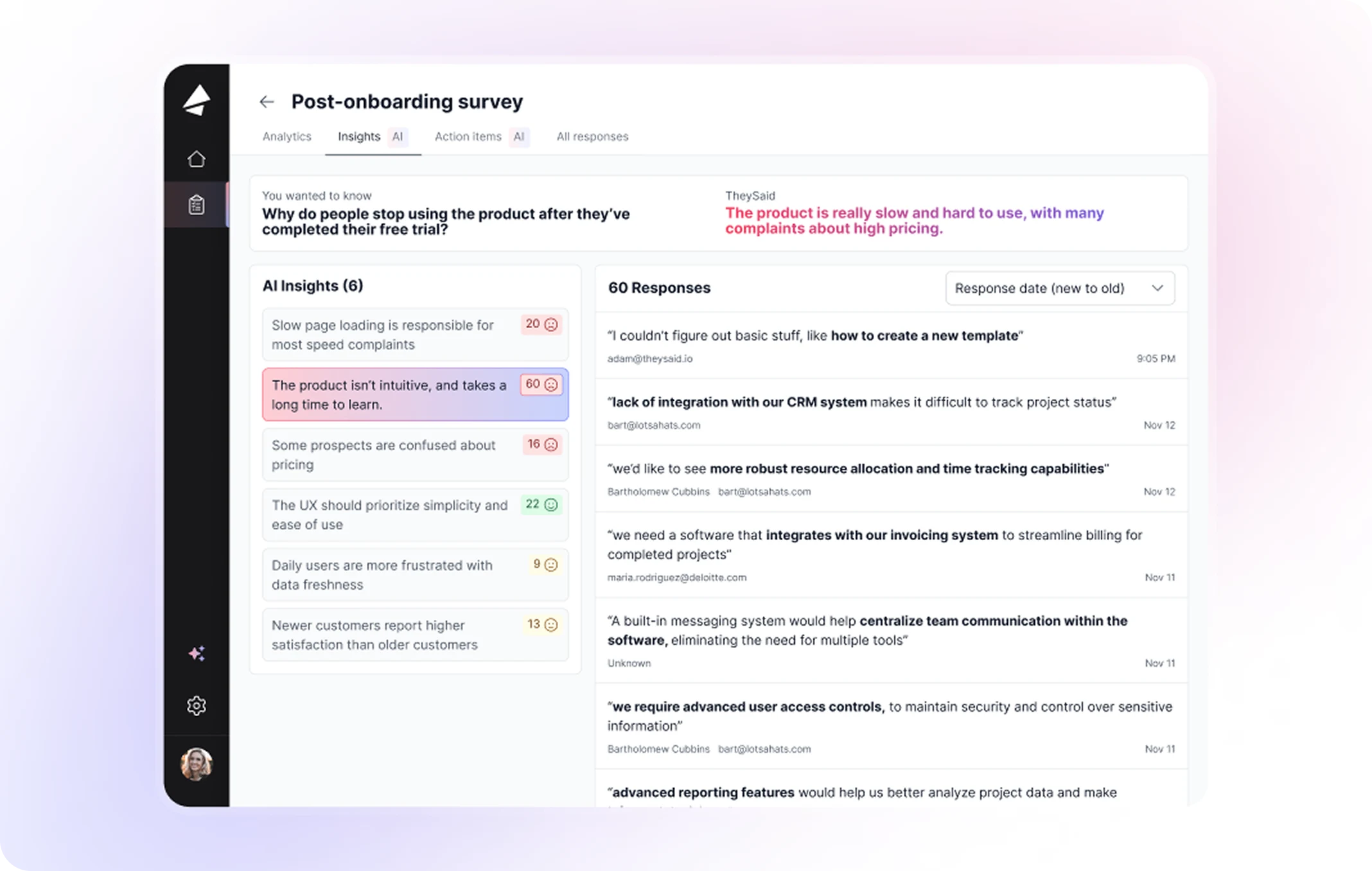

He outlines the essential stages of HCD: observation, ideation, prototyping, and testing. Each phase requires close contact with the end-user, not as a final step in validation but as a core driver of insight throughout the process. Observation, in particular, plays a critical role. Designers must learn to see the world as their users do, noting frustrations, workarounds, and expectations. This ethnographic approach replaces guesswork with empathy, allowing teams to surface the real problems that need solving.

Norman also emphasizes the importance of iterative design. Rarely is the first draft of a product the right one. Through cycles of prototyping and feedback, ideas are refined and mistakes are corrected. But iteration is only effective when it is rooted in user behavior and data. HCD places observation and testing at the heart of every decision, creating a continuous loop between the user’s experience and the designer’s output.

Perhaps most provocatively, Norman links human-centered design to innovation. He argues that the most groundbreaking products are not those that add more features, but those that solve real problems in new ways. In this context, design becomes a strategic tool, capable of transforming business models and user relationships alike. For startups navigating the complexities of digital products, this message is both aspirational and actionable: when you put the human first, success follows.